|

|

||||

|

|

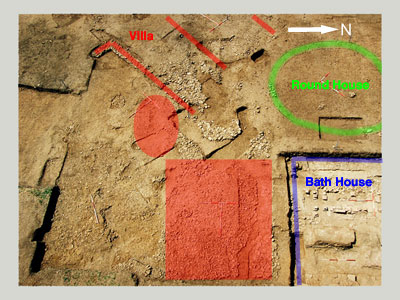

Introduction The scale and scope of this year's excavation has tremendously enhanced our ability to explain the overall plan, structural relationships and chronological development of the Whitehall villa estate. Some of the findings have highlighted hitherto unknown or little understood aspects of the site whilst other elements have confirmed conventional archaeological wisdom. In addition the quality and quantity of artefacts retrieved will provide an excellent insight into many social aspects of life at Roman Whitehall. The environmental and bone assemblages are particularly rich and will improve our understanding of the rural economy of this site. Undoubtedly the data recovered will have profound implications for research on other neighbouring Roman settlements in the surrounding areas. This year the archaeological emphasis has focused on five areas of research. These include the extensive stone surfaces and complex rubble spreads associated with the position of the eastern wing of the villa; the continuing excavation of the bath house and its environs which explored the fill of Room 3b, the spring and water supply regime utilised by the bath house and the drainage system underneath Room 4. Work continued on the area around the Proto-villa investigating the physical and chronological relationship of a series of pits adjoining the structure, which may have been contemporary with the building. Further investigation of the interior of the ditched enclosure, partially excavated in 2000, situated between the villa and bath house, was examined for evidence of any pre villa occupation. Finally an area of geophysical anomalies to the north west of the villa central range analogous with the field system and possibly containing a quarry or midden pit was also investigated. Villa Range Although our understanding of the interior of the central range of the villa has been severely limited by the systematic robbing and levelling undertaken in the 19th century, an extensive area of rubble containing worked stone suggested the survival of elements of an east wing. We had expected that the truncated and partial survival of these contexts would be extremely difficult to disentangle and that important layers of stratigraphy detailing the latest periods of occupation would have been lost. However, having cleaned and extended the area under observation it became increasingly apparent that significant structural material had survived. Most importantly we had the opportunity to explore occupational detail dating from the post Roman transitional period. Continuity of occupation is quite a rare phenomena on Roman sites but the evidence retrieved is indicative of a level of social cohesiveness surviving the demise of the Roman empire. However we should view the changing character of that activity as a response to the social, economic, cultural and political realities effecting the region which resulted in the creation of the kingdom of Mercia in the 6th centuries AD. The archaeological sequence of events suggests that at some stage during the very early 5th century the east wing of the villa was deliberately levelled. This may have been part of a piecemeal response to the general rate of decay and dereliction of the villa as elements of the buildings fell into disrepair or became redundant. Archaeological evidence of this general malaise has already been detected particularly in relation to the final phases of activity connected with the bath house. On levelling the area two distinctive metalled surfaces were prepared one of which was used to facilitate the construction of a timber phase of building whilst the other area was utilised as a courtyard space to service these structures. Post-Roman Timber Hall?

The main evidence for the Post Roman hall is two parallel lines of post pits for holding timber posts of considerable size. These post pits are orientated along an east west axis at a tangent to the east wing of the villa and are cut into the levelled masonry remnants of the villa east wing. The layout suggests that we are looking at the remains of a building on the scale of a dark age timber hall.

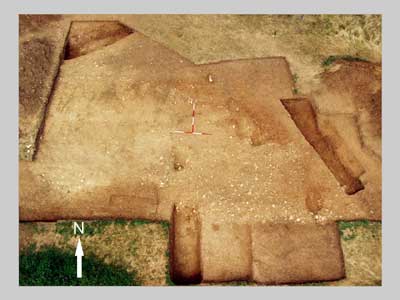

The probability of occupational activity during this period is further reinforced by the recovery of pottery of this date from elsewhere on the site. The importance of the hall within the context of post Roman occupation is difficult to assess and clarification of its role must await further excavation. However the existence of a timber hall also suggests continuity of communal life, which is consist with our interpretation of the social organisation, reflected in the villa buildings. Interestingly the timber posts contained within the post pits had all been burnt, presumably signifying the end of this phase of occupation. The reason for the burning of the hall cannot be determined and may have been as much to do with structural renewal and occupational shift as to warfare and conquest. Courtyard The courtyard surface had been covered with cobbles and graduated layers of gravel presumably to provide the timber hall with an external working area. Underneath these Post Roman surfaces are portions of walling and a flag stone floor. These features are consistent with the survival of structural elements of the east wing of the villa. These findings are extremely exciting because it suggests that although the upper sections of the building were levelled, the floors and foundations of the earlier Roman building may well have been buried and survive uncontaminated by later historical events. The excavation of the Post Roman phases and the possible subterranean elements of the villa will continue in 2003. Bathhouse The continued archaeological investigation of the bath house and the water supply and drainage system has also resulted in a great deal of information concerning the structural development of this building. Unfortunately the anticipated water tank, believed to be situated under the 4th century foundations of Room 4 did not materialise. However a system of culvert channels of an earlier phase of the bath house were located. The culvert system provided drainage for the bath house and also, more surprisingly, some elements of the villa range. The Room 4 foundation stratigraphy was fairly barren of artefactual material except for a 4th century Nene Valley Colour coated flagon which had been deliberately smashed and ritually deposited possibly to commemorate the changing role of the building or the structural alterations to the bath house. Connected to the drainage culverts via an opening in the north wall of the bath house we excavated a stone lined channel about 6 metres in length. The channel was covered by limestone capping stones and was connected to a sump or feeder tank for collecting water from the spring. Although only half a metre in depth and over a metre wide the clay lined pit appears to have acted as a reservoir and settling tank to supply a constant clean water supply to flush the drainage channels of the bath house. A partially excavated timber beam situated at the junction between the sump and the stone lined water channel may well have been part of a wooden sluice used to control the water flow. These findings hint at the sophistication of the water supply and illustrate some of the complexity of water management. Unfortunately the method of supplying water for the purpose of bathing is still very unclear. - reconstruction The excavation of Room 3b in the bath house has provided some excellent data on a major phase of reconstruction and development of the bath house complex during the late 3rd century AD. Excavation of the collapsed debris of the interior walls of the bath house and the foundation material supporting the raised floor level of Room 3b revealed a lower floor level associated with an earlier bath house phase. The context consisted of organic material overlaying an extension of the capped drainage culverts found under Room 4. Several coins were recovered focusing on the reign of Gallienus (253-268 AD), Cladius 11 (268-270 AD) and the Gallic empire of Postumus and Victorinus (259-270 AD). A few nearly complete vessels diagnostically datable to the 3rd century were also excavated. The context of the deposition of this organic material suggests that the layer was deposited over an extremely short period of time and probably is best interpreted as a opportunistic response to waste disposal for material from elsewhere in the villa complex. - organic finds Amongst the organic material retrieved were abundant amounts of animal bones, wooden artefacts and environmental evidence. We were able to identify elements of a wattle hurdle, barrel staves and the barrel bung. A discarded lathe plug from the production of a wooden bowl, sawn off-cuts and a fragment of an iron saw thrown away with the rubbish indicated carpentry waste. In addition the range of bones from this sealed context suggest an extensive dietary choice was available to those living on the villa estate at least in the late 3rd century. Notably among the traditional animal fare obtained from cattle, sheep, pigs and oysters were fragments of eggshells from chicken and duck eggs, bones of freshwater and saltwater fish and the skeletal remains of songbirds and bones from small edible mammals. The environmental material appears to be equally rich as is indicated by the survival of a peach stone. One is tempted to see the assemblage as kitchen waste collected from elsewhere around the villa which was dumped in room 3b to help build up the floor layer. However only the examination in the future by specialists of both the organic and bone material will provide us with the level of detail needed to fully understand and interpret the meaning of this deposit. A writing stylus was also recovered from the deposit and is of interest because it suggests that there was a degree of literacy amongst the villa community. It is hoped that further work in this area of the bath house will produced a lot more comparable evidence concerning the social interaction of people living on the estate. Round House Excavation inside the ditched enclosure of an area situated between the main range of the villa and the adjacent bath house revealed a robbed out circular foundation trench and post pads for a stone round house. The Round house is commonly found on most Northamptonshire villas and was part of the vernacular rural domestic building tradition. This building was over 9m in diameter and undoubtedly represents the earliest communal residential structure on this part of the site. Initial interpretation of the dating evidence obtained from contexts associated with the round house suggests a 2nd century date for construction. The Round house must have been utilised for at least two or three generations before becoming superfluous after the construction of the villa and bath house complex. The survival of the building at least into the early 3rd century is reflected in the way the villa and bath house complex do not encroach on the area but appear to respect its position. Nevertheless the round house must at some stage have become redundant because it was demolished and extensively robbed out for use elsewhere. Indeed the addition of Room 4 in the 4th century to the bath house appear to have made extensive use of reused stones boulders which are very similar to those identified in the round house foundations. Proto-Villa The excavated area containing the Proto Villa was extended in an effort to determine the full extent of the strip house and to look for further structural evidence. However during the removal of the topsoil several pits were discovered and sectioned. The pits contained extensive deposits of animal bones and appear to be contemporary with the occupation of the strip house. In particular deer antlers and long bones from cattle were quite conspicuous in the bone assemblages. It is possible that during the late 1st early 2nd century part of the villa population were involved in the working of bone of which some examples have been retrieved elsewhere on site. Unfortunately we are unable to gage the scale of the activity or comment on whether it was a full time or seasonal activity. Quarry? The excavation of the geophysical anomalies to the north west of the villa range produced very little artefactual evidence of the Roman period. Nevertheless the excavation established that neither a quarry or midden pit had existed in the area. The anomalies probably represent disturbance caused by modern subsoiling during either the 19th or 20th centuries. A pit of Roman date was located but its significance is obscure and further interpretation awaits future work on the surrounding landscape. However evidence of field boundaries probably dating to the time of 18th century enclosure which had been removed during the 20th century were recorded. Geophysics In addition to the excavation of the Whitehall Villa Northamptonshire Archaeology were commissioned to undertake more geophysical surveys to help answer three questions we had concerning the site itself and the surrounding landscape. It was important to find the extent of the Roman field systems and also to establish the limit of the cemetery associated with the Whitehall Warrior burial and to find out whether it was delineated by a ditched enclosure. The third area of interest to the north of the bath house was centred on the spring and the possibility of finding any archaeological evidence of a header tank that could have supplied water for bathing. Unfortunately the geophysical survey of a strip of land alongside Watling Street failed to detect any evidence of a continuos field system and the work undertaken on the spring only identified a pipe line associated with the 19th century hydraulic ram for pumping water back up the hillside. However the work on the anglo-saxon burial ground hinted that the cemetery was defined within a ditched enclosure. Cemetery? Unfortunately no archaeological evidence has been retrieved concerning burial practice from the Roman period and although a cemetery is to be expected its location remains unknown. The skeletal remains of the Whitehall Warrior excavated in 2001 were subjected to Radio carbon dating which indicated a late 7th to late 8th century date. Subsequent cultivation of the field has produced further evidence of other burials confirming the existence of a small cemetery. At the moment we know of five burials and the internments appear to be laid out in an organised linear pattern. The grave of the Whitehall Warrior has an east west alignment while an earlier grave of a woman through which it was cut followed a more north south alignment. It is possible that we have a burial ground that reflects the transition between pagan and Christian belief.

|

||||

|